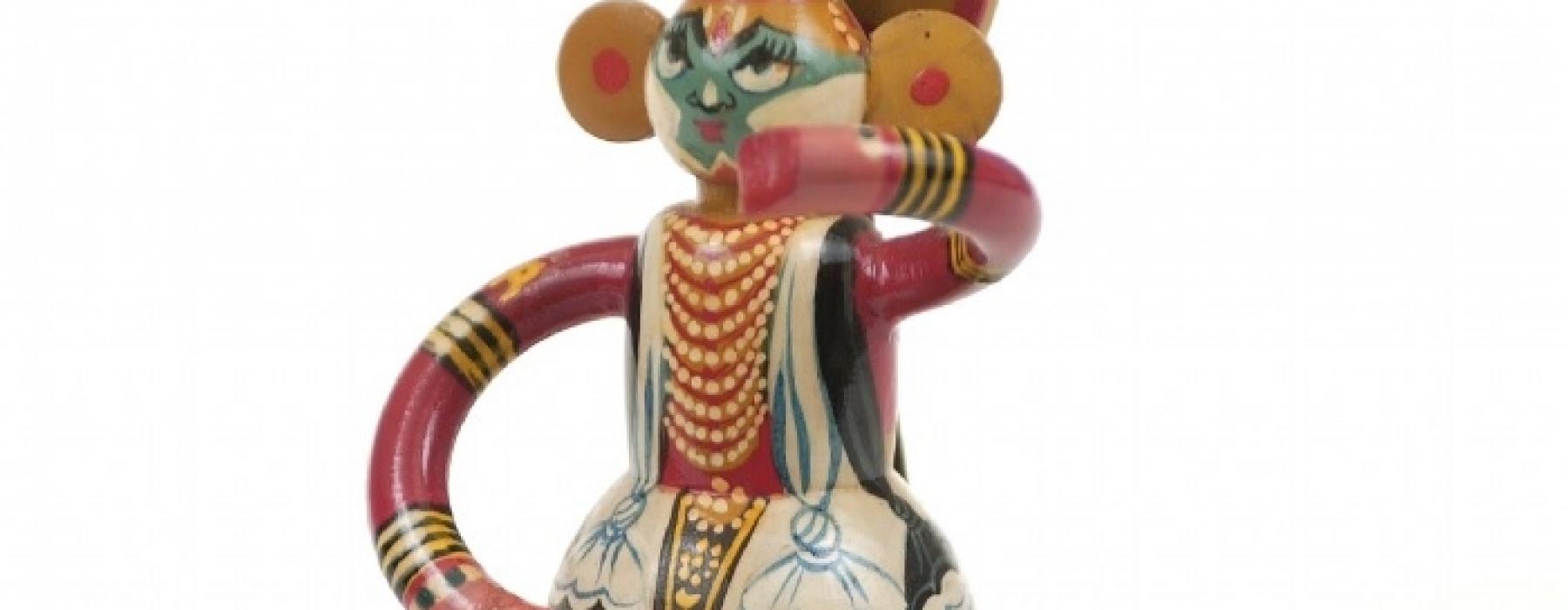

No one is certain of the origins of the particular style of lacquerware, but common knowledge suggests that its origins lie in 18th century Persia and toys have been produced using same techniques in the Channapatna region for over 200 years. The collection at National Museum of World Cultures contains unique examples. The costumes are depicted using graphic geometric forms indicating a jacket, an Indian skirt and a Kathakali costume. A female figure has long pleated hair made of wool. They have expressive faces. They could have been collected for this reason and as examples of facial typology. The Kathakali dancer is given a pair of arms posed for performance. These dolls also reveal their function as playthings, as imaginary figures assisting in role-play, transforming into characters in the process. Yet, this collection was never played with. Its purchase for a museum collection meant that the dolls became excerpts, and therefore metaphoric of their function. They represented other toys, became material evidences of toy-making practices, sui generis of the particular region and represented people that would play with them. While a western museological framing of the collection offers potential for insights into the ways of life of the people (from production to use), their delegation to the category of ‘tradition’ shows a continuity of this approach outside the museum. This is what I turn to now.

In 2005-06, Channapatna toys came under World Trade Organisation’s Geographical Indication (GI) protection. Toys produced in the region using the lacquerware technique have been patented, and therefore, legally preserved. Instigated by the Karnataka Government, GI protection secures the production and trade of the toys, while also assigning intellectual property rights to the producers. Tzen Wong and Graham Dutfield (2011, 195) have argued that GI can help nurture vernacular handicraft and shift consumer habits to support local craft. This has certainly been the case at Channapatna. Varnam, a design company, employs artisans in the region to produce modern designs for urban buyers (www.varnam.co.in). It has a flagship store in Bangalore and an online shop. It sells lacquerware items of all kinds, not just toys, but also home-ware, decorative items and jewellery, produced in the Channapatna style. Varnam showcased its designs at the London Design Festival in 2015, and describes them as “200 year old craft re-invented”, “quirky originals” and markets them as safe products using non-toxic pains. The company positions itself in relation to a national identity, evident in the phrase “VARNAM (colours) is an ode to colourful India”. Through this, an Indian identity is transferred onto the objects they market. While ethnographic objects in the museum and craft or design objects in the market consider local significance as one of their defining features, they are also given national identities. This is a process of signification. In the museum, this process is classificatory, a method of ethnography and national essentialism through material culture. In the market, the essentialised national identity lends the craft and design object a characteristic that can be consumed through the purchasable object.

The Varnam website contains photographs of the makers of its ‘designs’. They are unnamed and described as artisans (rather than as designers) but the artefacts produced are marketed as handcrafted design objects. Traditional techniques of making Channapatna toys are praised and a slow demise of the practice mourned. This, it argues, is due to a lack of innovation and import of mass-produced toys. It states that as a social enterprise Varnam helps keep craftswomen, the chief producers of the toys, employed. By positioning its role as one of intervention that drives innovation, Varnam refers to its repurposing of traditional toys as design. The producers are located as carriers of traditional skills, but Varnam staff as the designers.

The toys in the Museum collection represent their makers, users and Western ideas of Indian culture. Over fifty years on, the very objects have become a site of developmental concerns, as they embody values of culture, skill and craftsmanship. Both, museological and developmental agendas ethnographise the craftspersons. However, the object discourse in relation to the market differs. While the vernacular toy is protected as tradition in the museum and as heritage outside of it, and its extinction is feared in both contexts, in the market, it is seen to no longer meet the tastes of modern users. Innovation, a valued characteristic in design becomes the saviour of the craft in this discourse. 200 year-old techniques are now used to produce all kinds of functional designs. The visual elements of the toy (geometric forms, shapes, colours) that indicate Channapatna origins have been retained. But the toy, as stated on the Varnam website, has “crawled out of the nursery to perk up kitchens & living spaces!” It has been recuperated by the market as design.

Ethnographic, developmental and market approaches presume that as a traditional practice, the form of craft is fixed; that it has not changed. It would be a challenge to take a peek at Channapatna 200 years ago to see what was produced then, however, it is important to argue here, that while some of the techniques may have remain unchanged, the milieu of the producers and consumers of the toys will have changed and through this, their ‘designs’ will have changed. Therefore, could we not say that Channapatna toys may have always been ‘innovative’ designs? Design practice is often collaborative. Should their craft practice not be seen in relation to design practice? Should we not start associating the makers (as named individuals) with their designs? We would come a long way if we can achieve this. Design suggests a craft-design hierarchy and distinguishes the ‘skilled craftsperson’ from the ‘innovative Designer’. Revisiting this collection of toys and reconsidering their production shows that design is an intention. It is both a process and an outcome. The term design can also be understood as a translational term (a methodology posited by James Clifford in workshop Design Beyond the West: Ethnographic Collections and the History of Global Design, April 2016). This approach has allowed for a recasting of the toys in the study and opened up a space for a revisiting of categories.