To begin with some context: I first encountered the Quechan canteen while preparing a presentation for a panel on ‘Endangerment’ at the Caring Matters conference hosted by the Research Centre for Material Culture in Autumn 2020.[1] In the course of preparing the presentation I had settled on the concept of ‘selection’ as a means of linking the ideas of ‘care’ and ‘endangerment’ with the vexed questions that circulate in and around the ethnographic museum as a colonial institution, or ‘crime scene’ as a recent symposium described it.[2]

After all, questions of care are always, in some sense, questions of choice and thus of selection. Whether the choice concerns for whom or what we care, or whether the choice to care is in fact a choice already foreclosed by the very possibility of care, care and selection are conceptually inseparable. And, as literary theorist Ursula Heise has shown in Imagining Extinction, her book-length study of the cultural representation of endangerment among species, that question of selection is also central to a politics of endangerment where what is considered as endangered is never simply already given, but is always a matter of choice, and a choice that typically involves the sacrifice, or making killable, of others, of choosing not to care. (Heise)

But if the idea of selection seemed productive in thinking about care and endangerment, how might it help link those concerns with the role of the ethnographic museum?

It was in the process of puzzling out these connections and thinking about how it is often the ‘noise’ of the unselected that becomes most important in trying to understand museums as both expressions of and conversations with their collections that I came across the Quechan canteen.

That this particular item in the collection might be helpful in puzzling out the connections of care, endangerment and ethnography through the lens of selection was suggested first and foremost by the care with which its own selection for the collection had been documented. In addition to the name of the man who had chosen the pot, Herman ten Kate, the catalogue provided a vivid description of the circumstances of its acquisition, detailing how train passengers on the newly built Southern Pacific Railroad would stop at Yuma’s station to ‘stretch their legs’ whereupon ‘[e]nterprising Quechan women came to the platform and dickered with the travelers over the prices of home-made ceramics they offered for sale as souvenirs.’[3]

In Herman ten Kate too, it seemed the pot was connected to a man whose ideas about collection are vividly linked to his ideas about ‘selection’. On-line biographies describe an anthropologist concerned with the baleful influence of Western settlement on the indigenous cultures of North America; whose ‘observations on the impact of whites on Indian cultures constitute valuable documentation of the dilution of native life-styles.’ (Ten Kate, Travels). Further reading suggested the neo-Darwinian framework of racial hierarchies underpinning that concern with cultural endangerment: ‘[i]t is an inexorable law of nature (onwrikbare naturwet), that in the struggle for existence, the less privileged races must make way for the higher and ultimately disappear (te gronde gaan), so that the attempt to alter this will be futile’ (Ten Kate, Amerikaansche: 366-7) (Qtd. Hovens 158).[4] In Ten Kate in other words a neo-Darwinian faith in natural selection as the survival of the fittest imbues his activities as an anthropologist with a sense of the pathos of extinction: his purchase of the pot is framed as an act of ‘salvage anthropology’ – itself a peculiarly perverse expression of ‘care’.

But, if in Ten Kate there seemed to be an illustrative, possibly emblematic, constellation of questions of ethnography, endangerment and care, the catalogue also revealed that his was not the only possible framework for understanding Item RV-362-87. If Ten Kate ever knew the name of the Quechan potter who made, and, or, sold him the canteen, it is not recorded in the narrative of his travels. However, on the basis of further information in the catalogue entry it seems highly probable that the pot Ten Kate thought he was buying was very different from the pot he was actually sold.

For, as the catalogue explains, although Quechan women were renowned for their skills in ceramics, they did not make pottery canteens for domestic use and this canteen is in fact entirely unfit for purpose. As the catalogue notes: ‘[t]he Quechan made canteens of unfired or low-fired clay that could not contain water. Filled, they simply melted away.’ So too, its form is thoroughly syncretic, being modelled on the metal canteens of settler culture while the small looped handles supposedly intended for a rope would be too fragile to sustain its weight when filled with water. Further amplifying this sense of dissimulation, the catalogue also records a sense of disappointment that the decorative motifs have no discernable symbolic meaning, but instead are imitative of local flora and fauna: ‘[a]nd although early anthropologists asked, they were unable to solicit any deeper significance or spiritual origin for these motifs.’ Not only is the pot not what it seems, it stands accused of willfully withholding meaning – at least from the ethnographic eye.

So if Ten Kate believed he was rescuing a piece of Quechan culture before it was swept away by the inexorable march of Western modernity, it seems that the canteen he actually purchased might be more appropriately described as an early piece of ‘tourist art’ or what the catalogue carefully describes as ‘producten niet voor de lokale markt, maar b.v. voor toeristen’ – ‘products not for the local market, but, for example, tourists’. That a pot thought to have filled what anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot terms ‘the savage slot’ (Trouillot) was in reality already caught up in the currents of colonial trade is hardly surprising and the extensive scholarship on the colonial ideology of the ‘authentic’ aligns Ten Kate’s determination to discover native, or ‘inheemse’ artifacts with his devotion to describing the ‘typical’ physiognomy of the ‘peoples’ he visited.[5]

Rather than reclassifying the pot conceptually as tourist art, a category problematically implicated with the idea of the authentic, and a classification that also places the canteen within the narrative of endangerment and ‘corruption’ that frames Ten Kate’s understanding of his acquisition, I want to consider how those features of this canteen-that-is-not-a-canteen might extend an invitation to think of alternative connections between ethnographic objects, storytelling and care.

To begin with, accepting that invitation involves noticing that my focus on the narrative of race and extinction that informs Ten Kate’s motives for choosing the pot, obscures the ways in which the pot can equally have been said to have chosen Ten Kate, or, to have been the author of its own inclusion in the collection of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen. Specifically it obscures the creativity and invention of the Quechan women who, with the arrival of the railroad, repurpose their skills and practices as ceramicists to new ends. Women who literally turn a pot inside out so that it no longer holds water but now catches the gaze of passing railway travelers. Women who are, as such, already accessing the vector of modernity’s aesthetic of extinction, already understanding something about the nature of the ‘souvenir’.

And to ignore the way that this scene of selection is also one of transaction is also to ignore the ways in which the canteen is already shaped as an object of anthropological desire. As another incident in Ten Kate’s memoirs records, this desire seems to have been clearly recognized by his Quechan hosts who teased the Dutchman with his reluctance to pay a price that would reflect the value of the knowledge he thought he was acquiring: when he told Miguel, his Quechan intermediary and translator, that the prices being asked for native artifacts were far too high, Miguel’s replied, “No le gustan los Yumas?” – “Don’t you like the Yuma?”[6] The reasons why Linda Tuhuwai-Smith characterizes ‘research’ as ‘one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary’ (Tuhiwai Smith: 1) are plain to read throughout Ten Kate’s account of the Yuma, but in this incident the power of ‘research’ to blind the researcher seems excruciatingly clear, Miguel’s simple reply strikes directly to the heart of the ethnographic project. Unable to conceive of a relationship of reciprocity, or to see his interlocutors as anything other than prospective exhibits in a museum, anthropology is revealed as another form of dickering over price, and it is surely no coincidence that, of Miguel – his ‘trouwe Cicerone’ – he notes, ‘I could never find out his Indian name’ – ‘Zijn Indiaanschen naam kon ik niet te weten komen.’ (Ten Kate, Reizen: 111)

But to try and respond more adequately to the pot’s invitation to reflect on its own power to command a place within the ethnographic collection, I want to turn to the theorization of the relationship between endangerment, narrative and care in the work of the literary theorist, philosopher and archipelagic thinker, Sylvia Wynter. In her decades-long project of trying to imagine an idea of human consciousness capable of finding forms of care adequate to the catastrophic condition of a planet in crisis, of learning how to care for a planet rather than simply our kind, Wynter turns to the critical figure of homo-narrans, the human as story-teller. In this figure she encodes her understanding of being human in terms of a material and symbolic hybridity: of being at once a biological organism shaped by the instructions of genetic code and a creature whose sense and sensation of self is bound up with the set of stories that we tell ourselves about who we are. It is these ‘origin stories’, she argues, drawing on Frantz Fanon’s concept of sociogeny, which underpin the symbolic system and produce our patterns of aversion and desire, determining the direction and extent of that which can be recognized as a possible object of care.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, wherever European-based thought systems have prevailed, the dominant idea of the human, she argues has been based on the Darwinian origin story of ‘man’ as a biocentric organism: an origin story in which natural selection replaces Divine providence as the device for autotelic self-understanding (McKittrick and Wynter 36-37 and passim.). It is an origin story predicated on the construction of racial difference which, as in Ten Kate’s narrativization of the Quechan canteen, has immediate implications for the possibility of care. Insofar as Ten Kate’s narrative is predicated on the creation of racial hierarchies justified by the principle of selection, the Darwinian origin story forecloses the possibilities of care, either for other ‘kinds’ of human – whose fate is already known, or for an environment which exists simply to stimulate adaptation and the survival of the ‘fittest’.

If our origin stories, as Wynter suggests, determine the possibilities of our relation to the world and hence our capacity for reciprocity with that world, her figure of homo narrans prompts us to ask how might attention to the agency and authority of the Quechan canteen suggest possibilities for thinking new modes of connection and connectivity outside the Darwinian origin story inscribed in the ethnographic museum? Within biology, the origin story that all life is shaped by selection has been challenged most forcefully by evolutionary theorist Lynn Margulis, who points out that in much of the living world, it is not selection with its insistence on filiation and inheritance, but endosymbiosis, or the assimilation of already existing and heterogenous elements to produce new kinds of organism, that is the dominant ‘driver of evolution or metamorphosis’ (Endosymbiosis: Lynn Margulis).

This endosymbiotic origin story of combination and assimilation seems particularly relevant to the Quechan canteen shaped as it is out of Colorado river clay and ochre in conformance to the desire of passing travelers and European museums through a combination of elements drawn from an ever changing environment: the shape of a metal canteen, the pattern of a leaf. Indeed, given that the idea of extinction gathers its force from biology, it seems legitimate to push the idea of liveliness further into the biosemiotic realm and consider those decorative motifs not as failed symbolic communication but as a successful semiotic ruse – a pattern whose meaning is performative – appealing to the eyes in order to be taken up and carried away like the seeds of the plants from which they may, or may not, have been borrowed.

Reframing the canteen within a symbiotic story of assimilation then immediately restores the pot to a sense of liveliness denied by the Darwinian story of selection and extinction. However, the displacement of the Darwinian story of selection by a story of combination and assimilation does not exhaust the canteen’s power to question the ways in which origin stories regulate the relation of endangerment and care. For, by far the most significant fact about item RV-362-87 is the fact that it exists at all. Among the Quechen, the catalogue informs us, it was the custom to cremate ceramics and all other personal property with the dead, and as a result, the only ‘extant ceramics are commercial wares made for sale.’ The Quechan canteen’s survival, in other words, is also a story about survival, and about the different ways we might conceive survival including the possibility that the story of ‘the survival of the fittest’ might be a story of becoming out of place.

It is this out-of-placeness that thinking with Wynter enables us to identify as the real provocation posed to stories of selection by the Quechen canteen. For, in embodying the liveliness of things without a proper place, the canteen demonstrates the power of such things to disturb settled categories of place. In refusing to be consigned to the category of the indigenous, or Trouillot’s ‘savage slot’, it also frustrates the ethnographer’s attempt, in another of Trouillot’s memorable images, to peer over the ‘native’s shoulder’ (Trouillot: 132) and thus evades the epistemic grasp of the ethnographic museum. Instead, the canteen summons into being a new space that, thinking with Wynter, we might call a ‘demonic ground’: the ground, that is, which only emerges where the violence inflicted upon life by the exclusions of one origin story, makes it possible to conceive of a different conception of life and relation. A ground, or position, which will in Wynter’s words ‘thereby enable us to gain an external (demonic ground) perspective on the always already storytellingly chartered / encoded discursive formations / aesthetic fields, as well of, co-relatedly, our systems of knowledge.’ (McKittrick and Wynter: 32)[7]

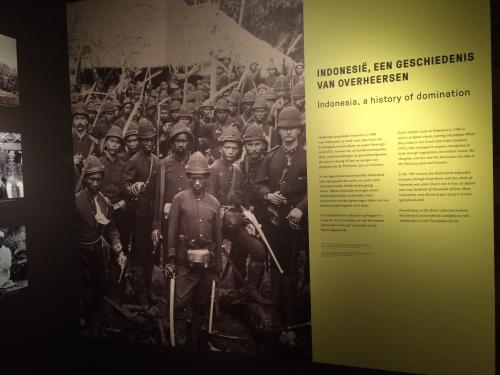

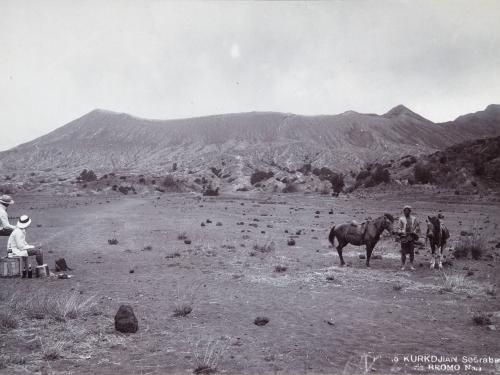

Wynter’s account of how the planetary system of exchange that emerged after 1492 produces spaces of mutual unintelligibility precisely through racialized categories such as the indigenous and the native is performed in miniature within Ten Kate’s narration of his visit to the Yuma (Wynter).[8] Once occupying a strategic position at a crossing of the Colorado river, Fort Yuma and the tribal lands of the Quechan had fallen into decline since the construction of the Southern Pacific railway. Formerly a major staging post on the ‘overland mail’ where travelers, after a lengthy and dangerous trip across the desert, would spend time before beginning the next stage of their journey, it was now just a place where passengers stopped for a moment to grab a snack and stretch their legs (Ten Kate, Reizen: 105-6).

In Ten Kate’s narrative the Yuma’s fate has, in other words, been sealed by their ejection from their traditional system of spatial relations and indigenization by the infrastructure of modernity. It is this overdetermining spatial logic that informs his account and conditions the possibilities of relationship with the Yuma he meets. It is this narrative logic that precludes him from recognizing and responding to the various opportunities to think alternative spatial relationships presented within his narrative itself. These include not only the world-wise Miguel, the potters and their pots, but the intermediary who translates his questions for Pasquale, the Yuma chief, a young man (painted from head to toe) who owed his perfect English accent to the fact that he had travelled the world as a clown in a circus and worked as a waiter in an American city, who spoke not only Quechan, English and Spanish, but also French and a little Italian (Ten Kate, Reizen: 113).

Within his narrative it is their intermediary function that marks them as figures of the demonic ground, the ground which connects and undoes the spaces which renders their cosmopolitanism invisible. The Quechan canteen-which-is-not-a-canteen, and which moreover, should not exist, is likewise an emissary of that demonic ground: shaped by the violence of the colonial system but which, thanks to its maker’s craft, resists allocation to the racialized spaces of that system. Instead the women dickering on the platform at Yuma in April 1883 call into being a world which in refusing to be partitioned into familiar spaces throws into relief the ways in which existing narratives of selection organized around ideas of endangerment work to preclude relationships of care. In presenting us in their handiwork with a vision of a world which is neither indigenous nor modern, their pot asserts its own claim to relationality by ventriloquizing the question posed by Miguel, what’s the matter, “No le gustan los Yumas?”don’t you like the Yuma?